Surgery in Epilepsy – How Advances in Human Neurology can benefit Veterinary Patients

M. Charalambous DVM GPCert(Neuro) RSci MRSB MRCVS 1 *

1UCL Institute of Neurology

*Corresponding Author (marios.charalambous.15@ucl.ac.uk)

Vol 1, Issue 1 (year)

Published: 09 Feb 2016

DOI: 10.18849/VE.V1I1.19

Epilepsy in humans is a common neurological disorder, following stroke, with a prevalence of 0.5% in the global population (de Boer et al., 2008). Approximately 30% of epileptic individuals do not adequately respond to antiepileptic drugs (drug-resistant epilepsy) (Engel, 1996) and continue to manifest seizure activity. Drug-resistant epilepsy dramatically lowers quality of life to the point that surgical resection is a viable option.

The aim of epilepsy surgery is to completely remove the epileptogenic area while avoiding neurological deficits (Zhang et al., 2014). Post-operative results have showed that seizure freedom has reached rates as high as 60% to 90% and 40% to 60 % in individuals with temporal and extra-temporal lobe epilepsy, respectively (Tellez-Zenteno, 2005). A recent systematic review (Hader et al., 2013) showed that there was a mortality of 0.4% and 1.2% in epileptic individuals with temporal and extra-temporal lobe surgical resection, respectively.

The same study reported severe neurological complications, mainly visual field defects, related to surgery in 4.7% of the patients. However, several studies have shown that epileptic patients who constantly manifest seizures (e.g., in drug-resistant epilepsy) have mortality rates three times higher compared to average population (Neligan et al., 2010, Sillanpaa and Shinnar, 2010). Epilepsy surgery might be considered as an inevitable treatment option in these cases.

Pre-surgical assessment has the most important role in the epilepsy surgery and is offered to patients with drug-resistant epilepsy or persistence of seizures despite administration of two anti-epileptic drugs in sufficiently high dosages (Kwan et al., 2010). Total resection or functional disconnection of the epileptogenic zone (EZ) which is area of cortex responsible for the generation of epileptic seizures, for achieving seizure-freedom while preserving vital cortex areas responsible for sensory processing and avoiding post-operative neurological deficits is the ideal outcome of surgery (Rosenow and Luders, 2001, Tellez-Zenteno, 2005). In order to succeed this outcome, precise localization of the EZ during the pre-surgical assessment is quite important. However, it still remains a challenge, mainly for extra-temporal lobe epilepsy (Tellez-Zenteno, 2005, Knowlton et al., 2008a, Knowlton et al., 2008b, Thomas et al., 2002, Papanicolaou et al., 2005).

However, the EZ is considered to be a hypothetical region as, currently, there is no diagnostic tool to locate it. One should indirectly detect it by locating other relevant zones, which are involved in generating the epileptic disorder or relevant electrographical and clinical symptoms, such as the irritative zone (IZ). The latter refers to the cortex responsible for generating interictal epileptiform discharges and it often provides an accurate definition of the EZ, although the EZ might cover a more or less extensive cortex area in some patients (Hunyadi et al., 2015, Rosenow and Luders, 2001, Knake et al., 2006, Schneider et al., 2012, Krishnan et al., 2015). Detection of the IZ is relatively accurate for locating the actual EZ, but the precise link between the two zones still remains vague (Badier et al., 2015).

The IZ can be evaluated by interictal non-invasive neuroimaging techniques such as scalp electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) or combination of them as well as invasive intracranial electroencephalography (icEEG); the latter has high sensitivity and specificity (Blount et al., 2008, Vulliemoz et al., 2011) and is considered as the “gold standard” for defining the epileptogenic area (Blount et al., 2008). Despite its diagnostic benefits, it is considered invasive, sample-limited, costly and risky (hematomas, acute bleeding or infections; Blount et al., 2008, Zhang et al., 2014).

The non-invasive neuroimaging techniques have improved the pre-surgical evaluation, surgical outcome and decision-making and managed to include a more extended number of patients who might not have been ideal candidates for pre-surgical evaluation in the past (Whiting et al., 2006). Although neuroimaging could not replace icEEG as far as the localization properties are concerned, a considerable amount of studies have shown that non-invasive neuroimaging could greatly reduce the need for icEEG (Knowlton et al., 2006, Zhang et al., 2014).

Electroencephalography (EEG)Scalp EEG is routinely used to record the electrical signals of the brain and is considered an effective method for defining the IZ (Rosenow and Luders, 2001) in approximately 70% of patients (Foldvary et al., 2001). EEG can be used either as a sole technique or combined with other ones. EEG source imaging (ESI), which involves combined results of EEG and MRI and computerized 3D analysis of the EEG source, has been used over the last years to localize the IZ with very promising results (Park et al., 2015, Plummer et al., 2008, Michel et al., 2004). Simultaneously recorded EEG/fMRI provides high spatial and temporal resolution data for the IZ, mainly by overcoming a few of the limitations of EEG with regards to sensitivity, and improved localization in challenging cases (Hunyadi et al., 2015). The EEG/fMRI technique is used to map haemodynamic epileptogenic-related networks in the brain, and, as a result it provides further valuable data for IZ localization (van Graan et al., 2015). Despite the promising results of the EEG/fMRI technique, in approximately 40%-70% of the cases, it could not adequately detect the IZ. Main reasons include the lack of interictal discharges in the EEG, lack of significant blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) signal changes in relation to their timing and presence of artifacts (Grouiller et al., 2011, Zhang et al., 2015).

Magnetoencephalograpy (MEG)MEG detects the magnetic signals of the brain and has also shown very promising results as a pre-surgical evaluation method (Knowlton et al., 1997, Stefan et al., 2000). MEG has an increased temporal resolution that makes it effective in localizing the IZ (Tellez-Zenteno, 2005). Compared to the electric signals recorded by scalp EEG, the magnetic signals are only minimally distorted from intervening tissues (i.e., skull and dura), resulting in an improved spatial resolution and sensitivity compared to scalp EEG that can be quite useful in guiding surgery (Ebersole and Ebersole, Ray and Bowyer, Kakisaka et al., 2012). In addition, a technique involving both MEG and EEG can detect neuronal activity at different orientation levels and therefore many studies reported the increased diagnostic value of the combined MEG/EEG in pre-surgical evaluation (Ebersole and Ebersole, 2010, Paulini et al., 2007, Zhang et al., 2015). Finally, MEG might be a predictive factor for a good surgical outcome in temporal lobe epilepsy (Assaf et al., 2004, Iwasaki et al., 2002). Localization accuracy of MEG has been considered to be close to that of the icEEG (Papanicolaou et al., 2005, Knowlton et al., 2006), although MEG is generally less available and needs more interictal spikes (Knowlton et al., 1997, Zhang et al., 2014). In on study (Papanicolaou et al., 2005), results from interictal MEG and ictal and interictal invasive video-recording EEG were compared in 41 surgical candidates (29 patients with temporal lobe epilepsy and 12 with extra-temporal lobe epilepsy). The study found that the overall localization accuracy of the IZ was 54% and 56% in icEEG and MEG, respectively (temporal lobe epilepsy: icEEG 55.2% versus MEG 65.5%; extra-temporal lobe epilepsy: icEEG 50.0% versus MEG 33.3%). The authors concluded that MEG might be as accurate as icEEG. In another study (Knowlton et al., 2006), MEG and icEEG were evaluated in 49 patients with partial epilepsy. They showed that MEG and icEEG could localize the IZ at sub-lobar level in 65.3% and 69.4% of the patients, respectively. However, in another study (Knowlton et al., 2008a, Knowlton et al., 2008b) in which MEG was compared to icEEG in 77 epileptic patients (39 with temporal lobe epilepsy, 33 with extra-temporal lobe epilepsy and 5 with non-localized epilepsy), it was found that MEG and icEEG localized the seizure focus in 61% and 70.1% cases, respectively. The same study found that MEG and icEEG failed to detect the seizure activity in 20.8% and 6.5% cases, respectively (Knowlton et al., 2008a). These results indicated that MEG might not be an ideal replacement of icEEG as far as the localization ability is concerned.

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI)Using fMRI in the pre-surgical evaluation of epileptic focus has shown promising results. Its current use involves identification of the eloquent cortex affecting visual, oral and motor functions that need to remain intact during surgery (Thornton et al., 2009) and it is commonly combined with simultaneous scalp EEG (Liu and He, 2008, Liu et al., 2006, He and Liu, 2008). Simultaneous EEG/fMRI correlates the epileptiform activity found on EEG with hemodynamic changes in BOLD in order to map the area of the brain responsible for the epilepsy (Hamandi et al., 2004, He and Liu, 2008, Gotman et al., 2006, Laufs and Duncan, 2007, Lopes et al., 2012). During standard EEG/fMRI method, identification of the timing of interictal spikes is performed on EEG and then each one of these impulses is combined with the hemodynamic response function in order to obtain a general linear model. The latter is then linked to the fMRI data using statistical methods to reach on an activation map (Lemieux et al., 2001). However, this technique has a few limitations, for example EEG artifacts during fMRI scan (Jacobs et al., 2009).

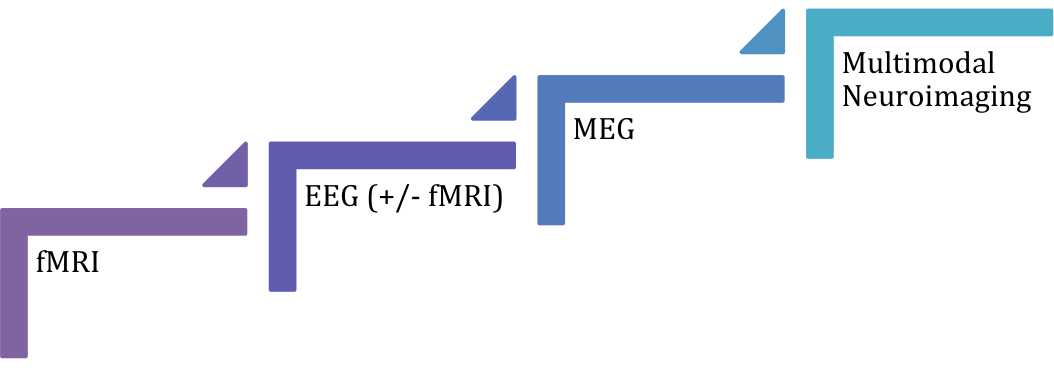

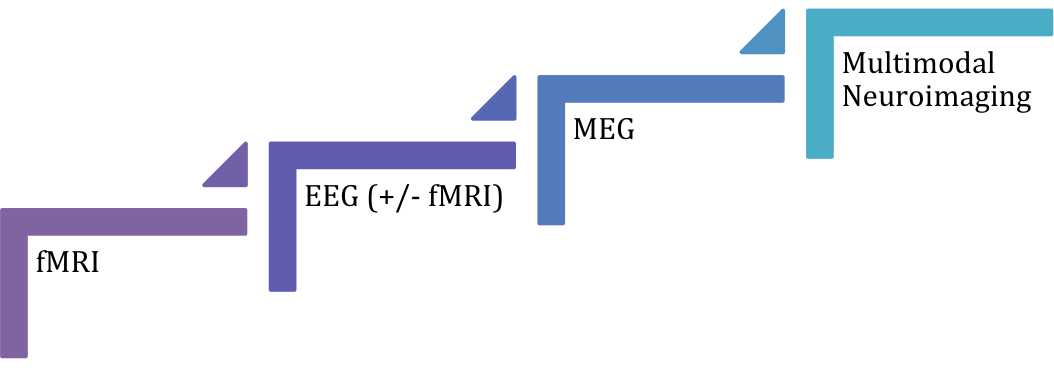

All in all, non-invasive functional neuroimaging techniques such as MEG, EEG, fMRI alone or in combination still might not be as efficient in localizing the EZ/IZ as icEEG, especially in extra-temporal lobe idiopathic epilepsy. However non-invasive neuroimaging could reduce the need for invasive pre-surgical monitoring in certain cases. The current evidence shows that multimodal approach (i.e. combination of techniques) might be the most accurate diagnostic method, followed by MEG, EEG, EEG/fMRI and fMRI (Figure 1); however results should be interpreted with caution until further studies with low overall risk of bias contribute to the current evidence.

Epilepsy in dogs has been found to be the most common chronic neurological disorder, with a reported prevalence of 0.5% - 5% in non-referral populations (Ekenstedt and Oberbauer, 2013, Podell et al., 1995). In UK, this prevalence was estimated to be 0.62% (Kearsley-Fleet et al., 2013). Drug-resistant canine epilepsy has been previously reported to affect as high as 30% of all dogs with idiopathic epilepsy (Lane and Bunch, 1990). Despite the fact that drug-resistant epilepsy can commonly occur in dogs, there is no or limited evidence behind surgical treatment options. There is one report in which experimental corpus callosotomy (i.e. surgical division of corpus callosum) in a very small number dogs with drug-resistant epilepsy was performed and showed encouraging initial short-term results (Bagley et al., 1996). However, the long-term outcome in these canine patients was not evaluated and further details related to the study design were not widely accessible. Due to this fact and the several limitations of the study, the overall risk of bias might be considered high. Therefore, surgical epilepsy has been inadequately described in dogs. The reason is mainly due to the fact that the EZ and/or IZ have not been extensively defined or described in animals and the lack of application of advanced functional neuroimaging techniques (e.g., EEG, MEG, fMRI). The latter are highly important in order to map and successfully localize the epileptogenic area. EEG has been used though in veterinary medicine to detect abnormal discharges in various diseases in dogs (Chandler, 2006) as well as interictal spikes in epileptic anaesthetized dogs (Jaggy and Bernardini, 1998, Srenk and Jaggy, 1996). The introduction of EEG in veterinary medicine as a routine diagnostic technique in the near future might change the current state and form the base of epilepsy surgery in animals.

All the supplementary files are available here.

Intellectual Property Rights

Authors of articles submitted to RCVS Knowledge for publication will retain copyright in their work, but will be required to grant to RCVS Knowledge an exclusive licence of the rights of copyright in the materials including but not limited to the right to publish, re-publish, transmit, sell, distribute and otherwise use the materials in all languages and all media throughout the world, and to licence or permit others to do so.

Authors will be required to complete a licence for publication form,and will in return retain certain rights as detailed on the form.